hen COVID-19 began accelerating across the country in March, the nation shut down in many ways.

But for those in the W. P. Carey community, the pandemic was a chance to step up. Using skills honed in the classroom and principles that have helped them succeed in business and beyond, they’ve found ways to support frontline workers, hungry families, and first-time homeschool teachers and distance learners.

The country and the world are facing the challenge of a lifetime, and these W. P. Carey and ASU students, alumni, and faculty members have risen to the challenge.

Share what you know

Share what you knowGreg Dawson, a clinical professor of accountancy, is praised on student-written review sites as “respected,” “caring,” and “hilarious.”

But Dawson admits that when COVID-19 closed campus, he was feeling more than a little helpless. “I joke that if I became shipwrecked on an island with other people, I’d be the first one eaten because I don’t bring any practical skills to the table,” he says. “I wasn’t someone on the front lines, like medical workers or restaurant workers.”

It wasn’t long before he realized that the 78 million parents who had become home-school teachers overnight might disagree about the value of the expertise he could bring to the moment.

He posted notes on his Facebook and LinkedIn pages — an audience of some 1,500 people — offering free math tutoring to kids whose parents might not feel entirely prepared to explain the nuances of improper fractions or complex statistics.

Parents were hungry for help, but it turned out that what they wanted wasn’t lesson-by-lesson teaching; instead, they were looking for tools that would help them assist their kids themselves. Dawson pivoted and began offering what these dozens of parents wanted. “It became a train-the-trainer approach,” he says.

He outlined the fundamentals of teaching: Help students see the broader context of a topic, so they understand not just how to solve a problem but also why it’s crucial. Teach using examples that feel meaningful to the student, whether their passion is horses or Pokémon. And if someone doesn’t understand the way you’re explaining something? Explain it differently.

In all, Dawson estimates he doled out such lessons to 50 people — and if homeschooling continues in the fall, he expects that the numbers might rise higher. He couldn’t be happier to help. “We can’t all be doctors in hospitals,” he says. “But we all have a skill that we can deploy right now. We can all become engaged in a valuable way.”

Share what you know

Share what you knowGreg Dawson, a clinical professor of accountancy, is praised on student-written review sites as “respected,” “caring,” and “hilarious.”

But Dawson admits that when COVID-19 closed campus, he was feeling more than a little helpless. “I joke that if I became shipwrecked on an island with other people, I’d be the first one eaten because I don’t bring any practical skills to the table,” he says. “I wasn’t someone on the front lines, like medical workers or restaurant workers.”

It wasn’t long before he realized that the 78 million parents who had become home-school teachers overnight might disagree about the value of the expertise he could bring to the moment.

He posted notes on his Facebook and LinkedIn pages — an audience of some 1,500 people — offering free math tutoring to kids whose parents might not feel entirely prepared to explain the nuances of improper fractions or complex statistics.

Parents were hungry for help, but it turned out that what they wanted wasn’t lesson-by-lesson teaching; instead, they were looking for tools that would help them assist their kids themselves. Dawson pivoted and began offering what these dozens of parents wanted. “It became a train-the-trainer approach,” he says.

He outlined the fundamentals of teaching: Help students see the broader context of a topic, so they understand not just how to solve a problem but also why it’s crucial. Teach using examples that feel meaningful to the student, whether their passion is horses or Pokémon. And if someone doesn’t understand the way you’re explaining something? Explain it differently.

In all, Dawson estimates he doled out such lessons to 50 people — and if homeschooling continues in the fall, he expects that the numbers might rise higher. He couldn’t be happier to help. “We can’t all be doctors in hospitals,” he says. “But we all have a skill that we can deploy right now. We can all become engaged in a valuable way.”

The only problem? It wasn’t always easy to know the best way to get supplies to the places that needed them most.

The executive director of ASU’s Luminosity Lab, Mark Naufel (BS Finance ’13, MS-BA ’15), and his students realized they could bridge the gap. “I remember having our first meeting on Zoom after the world shut down, and students were adamant that they couldn’t just sit around and wait,” Naufel recalls. “They wanted to be responsive to what was going on, and they immediately kick-started a few projects.”

One project that grew from those early conversations evolved into the PPE Response Network. Through a single website, health care providers submit their needs; individuals and groups pledge to meet those specific needs; and processors sterilize and deliver personal protective equipment to clinics, hospitals, and other sites.

The effort got off the ground and evolved with lightning speed. Within two weeks, students had designed, built, and deployed the network. Thanks to relationships that ASU had already developed with hospitals and medical providers, it was an easier task to connect creators ready to help with organizations that needed supplies.

To date, 149 contributors have created, processed, and delivered nearly 14,000 pieces of equipment.

And while Naufel says that it was satisfying to deliver orders to large organizations that needed them, he was particularly happy about the support his lab group was able to offer to small medical providers. “Unlike major hospitals, which have many different ways to try to access PPE, many smaller medical providers had no other means to get what they needed. We knew without our work, they’d be having a hard time.”

To raise the profile of their fast-casual Someburros restaurants over the years, for example, they bypassed big advertising campaigns in favor of sponsoring youth sports teams, supporting initiatives such as Teacher Appreciation Week, and raising funds for many local organizations. Tim Vasquez (BA Communications ’98) says it’s always been a win for everyone. “We do it that way because we know the money is going to kids, and it’s going to the community,” he says.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, it not only upended every aspect of the family’s restaurant business but also cut to the core of who they knew they were. They could adapt to takeout-only orders, but how could they continue to support their community when schools shuttered, sports canceled, and people lost their livelihoods?

The answer came when a longtime manager suggested they bring a party platter to a hospital near one of the restaurants. “We were scared and struggling at that point,” Tim admits. “But because of our culture of giving back, we knew it was a great idea. The doctors and nurses had been working so hard to take care of us, and we wanted to take care of them,” says Tim.

Soon, they opened up that idea to their customers. They launched a “Random Acts of Burros” initiative, in which customers could buy a food platter and have it delivered to frontline workers, including health care workers and firefighters. In all, the effort provided meals to more than 1,200 people.

Eventually, the company decided to go even bigger, says Amy Vasquez (BA Broadcasting ’03). “I remember the meeting,” she says. “Our small executive team was sitting around the table, all spread out, wearing masks. We were asking ourselves who we were and how we wanted to come out of this. What was important to us? What was in our hearts?”

In that meeting, they decided to provide 5,000 free meals — bean and cheese burritos, rice, chips, and salsa — to anyone in the community. Each of the 10 Someburros restaurants contributed 500 meals, and an all-volunteer team set up at Tempe Diablo Stadium to hand out the meals. It was a moment that wasn’t just good for the community — it also was an extension of the values that the organization has tried to instill in every one of its employees.

For George Vasquez (BS Business Administration ’74), the experience was unforgettable. “We brought the food to people’s cars so they could take it home to their families — whatever their need was — and it gave me so much pleasure to share that experience with them,” he says. “It was just something we wanted to do.”

And while their goal was simply to give back to the community that has supported the company for decades, it turned out to have a significant impact on their business. Social media mentions and local media coverage exploded, and customers flocked to their restaurants.

While the Vasquezes know that things may not return to normal for some time, they feel confident that their business will be able to come through the crisis intact. “The community wanted to support us because they saw us supporting other people,” Tim says. “They saw that [our efforts] were coming from a good place.”

Spread the word

Spread the wordEdward “Ned” Wellman, associate professor of management and entrepreneurship, has spent years studying the principles of successful leadership. He knows that great leaders rise to the occasion in a crisis — and that people can show true leadership no matter what their titles are.

In spring, he provided an object lesson in both.

After spending a week teaching students about how people can influence others even when they don’t have formal leadership authority, Wellman created an assignment that would illuminate that idea. He asked students to form groups and work to raise money for coronavirus-related charities. He seeded the efforts with a $10 donation for each group from his wallet. “This was an opportunity for students to practice leading positive change, even if the circumstances weren’t ideal for some people to give money,” he says.

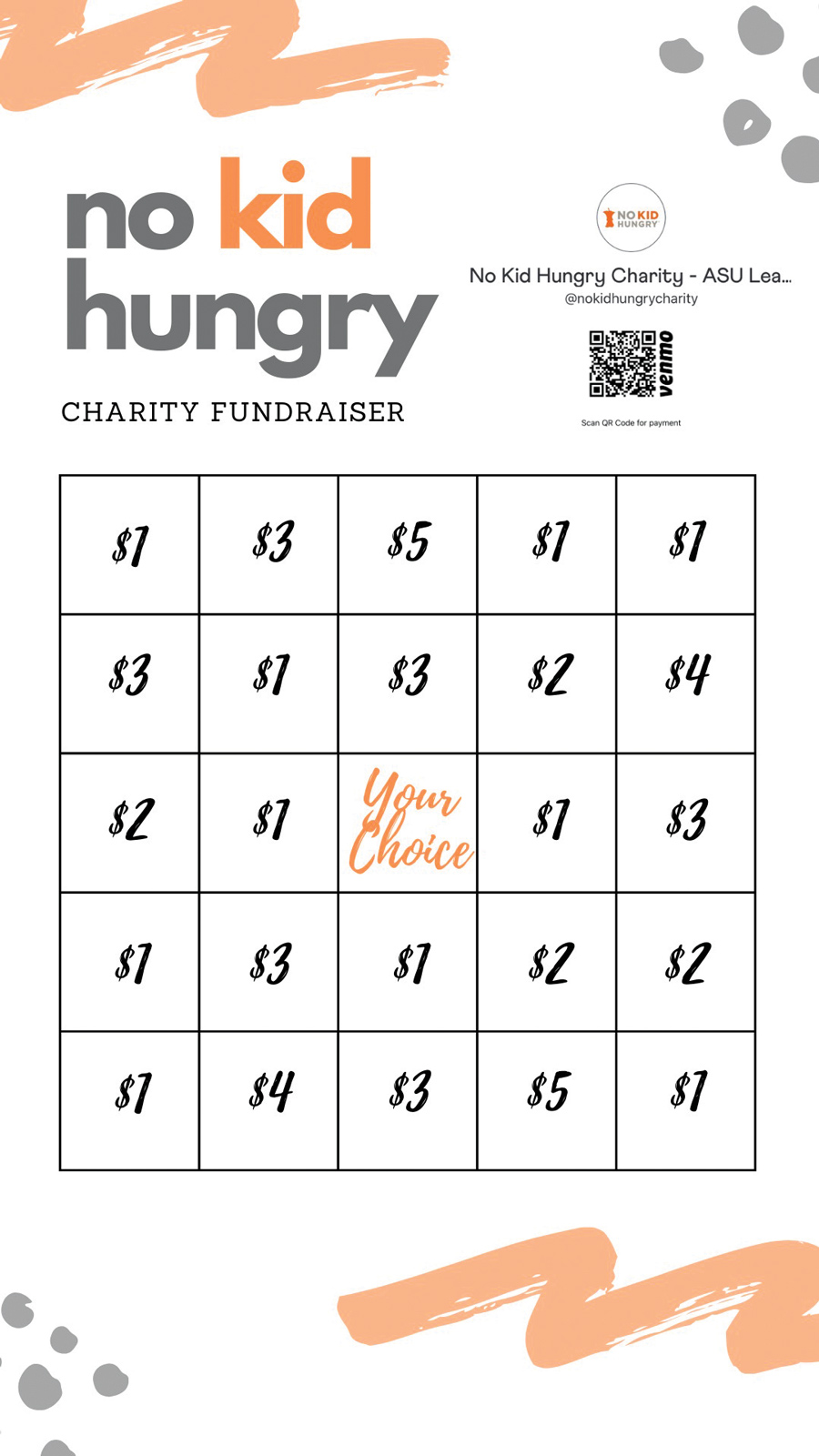

McKenna Anderson (BS Management/BA Business Communication ’20) was part of a group of five dubbed DJ LAM. The team was able to pair good ideas it had learned from other fundraising efforts with a significant social media push to raise money for No Kid Hungry, a charity that provides free meals to children. “I was in a sorority that had used ‘bingo boards’ for our fundraising, and we did [something similar] for our project,” Anderson says. DJ LAM created a memo explaining the cause, along with a bingo board that contained boxes with donation amounts from $1 to $5. Anyone who donated got tagged on the post, and the message spread quickly.

McKenna Anderson (BS Management/BA Business Communication ’20) was part of a group of five dubbed DJ LAM. The team was able to pair good ideas it had learned from other fundraising efforts with a significant social media push to raise money for No Kid Hungry, a charity that provides free meals to children. “I was in a sorority that had used ‘bingo boards’ for our fundraising, and we did [something similar] for our project,” Anderson says. DJ LAM created a memo explaining the cause, along with a bingo board that contained boxes with donation amounts from $1 to $5. Anyone who donated got tagged on the post, and the message spread quickly.

While the project was proving successful on its own, a friendly intragroup competition helped increase donations even further, says Alve Diaz (BS Management ’20). “We were all trying to get the most names on the board,” she says.

While the project was proving successful on its own, a friendly intragroup competition helped increase donations even further, says Alve Diaz (BS Management ’20). “We were all trying to get the most names on the board,” she says.

By the end of the project, the team had raised $535, enough to provide more than 5,000 meals.

But the group didn’t stop there: They’d kept their boards active. As of mid-June, they had raised just shy of $1,000. (The class as a whole raised over $1,500.)

Anderson and Diaz find a little friendly competition can help raise even greater contributions.

Spread the word

Spread the wordEdward “Ned” Wellman, associate professor of management and entrepreneurship, has spent years studying the principles of successful leadership. He knows that great leaders rise to the occasion in a crisis — and that people can show true leadership no matter what their titles are.

In spring, he provided an object lesson in both.

After spending a week teaching students about how people can influence others even when they don’t have formal leadership authority, Wellman created an assignment that would illuminate that idea. He asked students to form groups and work to raise money for coronavirus-related charities. He seeded the efforts with a $10 donation for each group from his wallet. “This was an opportunity for students to practice leading positive change, even if the circumstances weren’t ideal for some people to give money,” he says.

McKenna Anderson (BS Management/BA Business Communication ’20) was part of a group of five dubbed DJ LAM. The team was able to pair good ideas it had learned from other fundraising efforts with a significant social media push to raise money for No Kid Hungry, a charity that provides free meals to children. “I was in a sorority that had used ‘bingo boards’ for our fundraising, and we did [something similar] for our project,” Anderson says. DJ LAM created a memo explaining the cause, along with a bingo board that contained boxes with donation amounts from $1 to $5. Anyone who donated got tagged on the post, and the message spread quickly.

McKenna Anderson (BS Management/BA Business Communication ’20) was part of a group of five dubbed DJ LAM. The team was able to pair good ideas it had learned from other fundraising efforts with a significant social media push to raise money for No Kid Hungry, a charity that provides free meals to children. “I was in a sorority that had used ‘bingo boards’ for our fundraising, and we did [something similar] for our project,” Anderson says. DJ LAM created a memo explaining the cause, along with a bingo board that contained boxes with donation amounts from $1 to $5. Anyone who donated got tagged on the post, and the message spread quickly.

While the project was proving successful on its own, a friendly intragroup competition helped increase donations even further, says Alve Diaz (BS Management ’20). “We were all trying to get the most names on the board,” she says.

While the project was proving successful on its own, a friendly intragroup competition helped increase donations even further, says Alve Diaz (BS Management ’20). “We were all trying to get the most names on the board,” she says.

By the end of the project, the team had raised $535, enough to provide more than 5,000 meals.

But the group didn’t stop there: They’d kept their boards active. As of mid-June, they had raised just shy of $1,000. (The class as a whole raised over $1,500.)

Anderson and Diaz find a little friendly competition can help raise even greater contributions.