— Michael Jordan

he F-word — yikes! When I first heard the theme for this issue, I did a double take. Not because it’s a little risqué, but because it’s a little risky. Who wants to read about failure? Yet failure is behind almost every success. And reading about failure is also reading about resilience, lessons learned and, ultimately, new ways of doing business. That’s exactly what we want to celebrate at W. P. Carey.

In this issue, you will hear from our alumni who have faced various failures on their roads to success. No matter if they were hobbled by bad decisions, bad timing, or just plain bad luck, these brave entrepreneurs and innovators have had to pick themselves up and learn from their mistakes before trying again. We like to think they learned that from us — after all, academia itself is wrought with failure. Did you know that fewer than 10% of academic research papers are accepted at the major journals in the field? Failure is so baked into what we do that a marker of theoretical rigor is something called “falsifiability” — or whether the theory can be proven untrue.

This acceptance of failure as part of the process is why we are unafraid to try new things at W. P. Carey, and why we are proud to be a part of ASU’s culture of excellence in innovation. Last fall, U.S. News & World Report named ASU No. 1 in Innovation for the fifth year running. Accolades like this are deeply meaningful to all of us, and important to furthering the reputation and excellence of the school. You can read more about the role of rankings — and the pivotal part you play as alumni — on page 20.

While ASU as a whole is a showcase for innovation, we believe W. P. Carey makes a major contribution to the university’s prestige with new programs like our Fast-track MBA, our Interdisciplinary Applied Learning Labs that partner with other graduate programs on campus, and our groundbreaking Teaching & Learning program that is leading transformative conversations in B-schools across the globe.

Our success in all we do is born from our failures, and I bet that’s true for many of you, too. I hope your time at W. P. Carey taught you to take smart risks, to learn from setbacks, and to plow ahead with renewed verve for your passions. And if it will make you feel better, don’t be afraid to mutter a quick F-word. Failure happens to the best of us!

Warm regards,

Amanda Kichler (Marketing ’19)

Dennis Kost (BS Computer Information Systems ’98)

Rani Sweis (BS Global Business ’09)

Tim Krueger (BS Business Administration ’84)

Kaleigh Feuerstein (BS Marketing ’21)

Mariela Lozano Porras (BS Marketing ’22)

Volume 7, Issue 2, Spring 2020

Dean

Amy Hillman

Associate Dean, Graduate Programs and External Relations

Kim Steinmetz

Director of Alumni Relations

Brennan Forss

Manager of Alumni Relations

Theresa Shaw

W. P. Carey Alumni

wpcarey.asu.edu/alumni

Facebook

facebook.com/wpcareyschool

LinkedIn

wpcarey.asu.edu/linkedin

Twitter

@WPCareySchool

Shay Moser

Creative Director

Paula Murray

Staff Contributors

Emily Beach, Colin Boyd, Perri Collins, Mary Beth Faller, Ashley Hew, Hannah O’Regan, Madeline Sargent, Connor Wodynski

Contributors

Joe Bardin, Kim Catley, Andrew Clark, Claire Curry, Matthew Dewald, Melissa Crytzer Fry, Jane Larson, Betsy Loeff, Erin Peterson, David Schwartz, Jenn Woolson

Photographers

Mark Lipczynski, W. Scott Mitchell, Shelley Valdez

Managing Editor

W. P. Carey School of Business

Arizona State University

PO Box 872506

Tempe, AZ 85287-2506

Changes of address and other subscription inquiries can be emailed to:

editor.wpcmagazine@asu.edu

W. P. Carey magazine is a publication of the W. P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University © 2020

Send editorial submissions and letters to:

editor.wpcmagazine@asu.edu

fter graduating from ASU’s W. P. Carey School of Business, Audree Lopez (BS Marketing ’15) is living her dreams in New York City. At 27, she’s already been a part of the fashion industry for 10 years — building a career with both paid and unpaid internships, as well as client work with the likes of Marc Jacobs, Good Housekeeping, and CoverGirl.

Lopez’s career hasn’t always gone seamlessly, however. When she decided to move across the country to pursue her goals, she imagined her path going a little bit differently. As Lopez settled into the fashion and editorial department at Glamour, O, The Oprah Magazine, and Redbook, she started to question if the corporate world was really for her. Eventually, she decided to start over and joined Alice + Olivia as a freelance stylist, and then began contributing to StyleCaster.com as an editor.

Reflecting back on the highs and lows, as well as making it to the other side, has given Lopez the perspective to realize that failure isn’t final. “Each failure has challenged me, pushed me to work harder, and given me the opportunity to learn something new about the fashion industry,” she reflects. “Don’t look at failures, challenges, or hardships in your career as bad things. Be objective and ask yourself, what did you learn from this experience and how can it prepare you for next time? Everybody makes mistakes and what will make you successful is the ability to pick yourself up, learn from each experience, and move forward.”

Today, Lopez is using her own advice to forge ahead with her freelance work and businesses, including Audree Kate Studios, Fashion Fundamentals (a digital fashion course launched in 2018), and the blog she started in college, Simply Audree Kate.

Focused on remaining steady in who she is while also providing a fresh perspective, Lopez takes to social media to showcase thrifting hauls, sewing tutorials, and blog posts — all designed to help aspiring fashion professionals stay ahead of the game and succeed in a competitive industry.

ALL THINGS WPC

he W. P. Carey Master of Science in Business Analytics (MS-BA) exposes students to knowledge that helps them develop an intuition on how to improve specific business functions. During the nine-month program, students dive into 10 courses culminating with an applied project.

“Over the past five years, we have worked on over 150 applied projects with 50 companies,” says Hina Arora, clinical assistant professor and MS-BA director of experiential analytics. “Many students go on to accept internships and full-time positions with the clients they work with. Forty percent of participating organizations have collaborated with us over multiple years, which we believe is a strong testament to the value of this partnership.”

Vivek Singh (MS-BA ’16) valued the experience as a student, and now as an alumni adviser. During spring 2018 and 2019, while working at Ports America, Singh facilitated and sponsored MS-BA applied projects and mentored more than 20 students. Each project gave students the chance to discover actionable insights that could help with predicting the future of business goals. At the end of the project, students presented to stakeholders on their results.

ALL THINGS WPC

t W. P. Carey, we know that business is personal. Our students learn that, too, and take their responsibility to build supportive and inclusive communities seriously. The Hispanic Business Alumni chapter (HBA), founded in 1982, is a textbook example of alumni giving their time, talent, and treasure to uplift the next generation of W. P. Carey students.

Mario Solorzano, president of the HBA, explains the many ways the chapter supports students, including scholarships, mentorship, and a network of more than 3,000 active members. “We try to foster community between current students in the Hispanic Business Student Association (HBSA) and alumni,” he explains. “It isn’t just for students or just for graduates, but a way we can connect multiple generations of W. P. Carey students toward a common purpose.”

More than 100 people attended the most recent HBA alumni mixer in Phoenix. The chapter also holds several fundraisers each year that have supported more than $1 million in scholarships to date. This year, 24 W. P. Carey students are receiving financial support from the HBA. The annual Noche de Loteria takes place every fall, and is the group’s signature event alongside Mariachi Fest and the Sparky Classic Golf Tournament.

ALL THINGS WPC

e are pleased to congratulate Blake Ashforth, Horace Steele Heritage Chair in the Department of Management and Entrepreneurship, on being honored with the highest faculty award possible. Reserved for the top 2% of faculty, Ashforth was one of five ASU professors to receive Regents Professor status in November 2019.

“Arizona State University is proud to count these deserving scholars among our world-class faculty,” ASU President Michael Crow said of Ashforth and fellow honorees. “Their work meaningfully expands our knowledge of the world, and our university community is fortunate to benefit from their experience and leadership.”

Ashforth, a faculty member since 1996, conducts thought-provoking research on topics of relevance to every business environment, including how new employees find identity and meaning in the workplace, why things like corporate corruption and job burnout happen, how organizations and individuals affect each other, and why respect is important to employees.

We are proud and thankful for your contributions to the school and the world. Bravo, Blake!

. P. Carey Professor of Management and Entrepreneurship Luis Gomez-Mejia has enjoyed a lot of success: He’s an ASU Regents Professor and a member of the Academy of Management’s Hall of Fame, and has again been named a highly cited researcher by Web of Science — a recognition he has now received for eight straight years.

With its designation, Web of Science honors the world’s most influential researchers who have produced multiple highly cited papers over the previous decade — those that rank in the top 1% by citations for field and year.

As 2019 concluded, Gomez-Mejia had accumulated about 36,000 citations to his research, a feat that few members of the Academy of Management (the main academic association of the field of management) have been able to match. Yet when asked about these impressive accolades, Gomez-Mejia is quick to point out the failures that led to such success: He estimates that of his 260 published journal articles, there have probably been 600 rejections. One paper was turned down 10 times before it was accepted. Yet Gomez-Mejia pushed on. “You have to believe in what you’re doing, even when others might not see the value yet. And then you balance that belief by engaging with the rejection and asking yourself, ‘How can I make this research better?’ Then, you try again.”

e are pleased to announce a new degree program — the W. P. Carey Fast-track MBA, which makes it possible to revitalize your career in as little as 12 months and just two classes per week.

“We’re always looking at ways to make education more accessible,” says Dean Amy Hillman. “ASU and the W. P. Carey School have a reputation for innovation, and the Fast-track MBA is another way we can use our resources to offer a solution for students who might have thought there were too many obstacles to getting an MBA.”

Scheduled to launch in August 2020, the new program caters to professionals with an existing master’s degree in a business discipline. Eligible alumni and friends are welcome to apply.

Learn more: wpcarey.asu.edu/fast-track

Many of our upcoming events are impacted by COVID-19. To see up-to-date information on what has been canceled, moved to a virtual format, or postponed, please visit wpcarey.asu.edu/alumni-events. To learn more about the university’s response to the novel coronavirus, visit coronavirus.asu.edu.

APRIL 1

Learn to compete through the strategic use of service and an unrelenting focus on the customer. Enter WPCALUMNI for your 15% alumni discount. wpcarey.asu.edu/cts

APRIL 9

Join the Economic Club of Phoenix for a special lunch honoring 2020 Executive of the Year Christian Koch, president and CEO of the Carlisle Companies. wpcarey.asu.edu/ecp

APRIL 17

Our popular Back to Class lecture series invites alumni to hear from and engage with esteemed faculty across disciplines. Hosted online only. wpcarey.asu.edu/alumni-events

MAY 4

Celebrate the achievements of ASU grads who own and lead successful, innovative businesses across the globe. alumni.asu.edu/events/sun-devil-100

MAY 5

Get your first look at the Greater Phoenix economy, and how the national and state economies hang in the balance in an election year. wpcarey.asu.edu/ecp

MAY

11-12

Reunite with classmates and campus landmarks from 50 years ago. This special, all-about-you celebration will be hosted during ASU Commencement 2020. alumni.asu.edu/events/golden-reunion

MAY 13

Hear from world-renowned faculty, connect with fellow alumni, and gain fresh business insights — for free. Hosted in person and online. wpcarey.asu.edu/alumni-events

JUNE 11

Get another round of fresh, free insights to kick-start your brand, business, or professional development. Hosted in person and online. wpcarey.asu.edu/alumni-events

ack to Class enables W. P. Carey alumni to learn from world-renowned faculty, expand their network, and gain perspectives of immediate relevance. We hope to see you in person (or online!) for one of our upcoming events. Clinical Professor John Eaton has been a Department of Marketing faculty member since 2006. With research interests including marketing management, brand image and personality, and more, we can’t wait to see what topic Eaton delves into during Back to Class this April.

Taking a behavioral approach to strategic management, Associate Professor Jonathan Bundy’s research focuses on the social and cognitive forces that shape organizational outcomes and behavior. Get the inside scoop at Bundy’s Back to Class session in May.

Associate Professor of Management and Entrepreneurship Mike Baer conducts research focused on trust, fairness, ethics, and impression management. Explore some of his recent work on p. 26, and head back to class with Baer this June.

— Tom Patterson

(BA Interdisciplinary Studies ’02)

— Erin Fujimoto

(BS Finance ’02)

alumni profile WPC

o adjustment needed.”

That’s the motto of cult favorite underwear company Tommy John, which was co-founded by ASU alumni Tom Patterson and Erin Fujimoto. Luckily, the duo didn’t apply that motto to their own lives: While Patterson was bothered by an undershirt that wouldn’t stay tucked in, Fujimoto had an itch to work at something she felt passionate about, and both made a few adjustments to create better lives for themselves.

After graduating from W. P. Carey in 2002 with a degree in interdisciplinary studies, Patterson took a job as a medical device salesman. “I wore undershirts, and I was tailoring my suits and shirts and I thought, ‘Why doesn’t anyone make an undershirt that’s not baggy and boxy and stays tucked in?’” That question sent him down a path of wanting to find a better way to make them. Growing up in South Dakota, he’d had an entrepreneurial spirit from the start, running lawn-mowing and snow-blowing businesses as a kid.

alumni profile WPC

— Tom Patterson

(BA Interdisciplinary Studies ’02)

— Erin Fujimoto

(BS Finance ’02)

o adjustment needed.”

That’s the motto of cult favorite underwear company Tommy John, which was co-founded by ASU alumni Tom Patterson and Erin Fujimoto. Luckily, the duo didn’t apply that motto to their own lives: While Patterson was bothered by an undershirt that wouldn’t stay tucked in, Fujimoto had an itch to work at something she felt passionate about, and both made a few adjustments to create better lives for themselves.

After graduating from W. P. Carey in 2002 with a degree in interdisciplinary studies, Patterson took a job as a medical device salesman. “I wore undershirts, and I was tailoring my suits and shirts and I thought, ‘Why doesn’t anyone make an undershirt that’s not baggy and boxy and stays tucked in?’” That question sent him down a path of wanting to find a better way to make them. Growing up in South Dakota, he’d had an entrepreneurial spirit from the start, running lawn-mowing and snow-blowing businesses as a kid.

— Michelle Cirocco (MBA ’08)

decade ago, Aaron Matos (BS Management ’95) was riding high on eight straight years of 100% growth with his human resources web service, Jobing.com. The company had grown to have a presence in six markets, and he was rolling out the addition of a dozen more.

“Then we overexpanded right in what was the teeth of the recession” of 2008, Matos says. “We won what I affectionately call ‘the bad timing award.’” What had appeared to be a sea of plenty dried up in front of him as the economy crashed and hiring markets disappeared.

“You go from being a genius to an idiot in about three months,” he says.

If you visit any company’s website, you’re unlikely to read about moments like this, when everything’s gone wrong. Executives’ bios on “About” pages dependably construct a concurrent narrative in which people go from one success to another. Failure is not part of the story.

But as these alumni from ASU’s W. P. Carey School of Business will tell you, failure inevitably is part of the story. Bad timing, wrong choices, misaligned skillsets, and misunderstood problems all come with the territory when leading a business. As their experience shows, what matters is how we fail, what we learn from it, and how it makes businesses stronger and leadership more capable over the long term.

Take Matos as Exhibit A. Today he is the founder and CEO of Paradox.ai, which provides an assistive intelligence platform that helps companies improve their interview acceptance rates, exceed hiring goals, and reduce hiring time. It serves more than 400 organizations in more than 60 countries. Among them: McDonald’s, Delta Air Lines, and CVS Health.

— Michelle Cirocco (MBA ’08)

— Michelle Cirocco (MBA ’08)

decade ago, Aaron Matos (BS Management ’95) was riding high on eight straight years of 100% growth with his human resources web service, Jobing.com. The company had grown to have a presence in six markets, and he was rolling out the addition of a dozen more.

“Then we overexpanded right in what was the teeth of the recession” of 2008, Matos says. “We won what I affectionately call ‘the bad timing award.’” What had appeared to be a sea of plenty dried up in front of him as the economy crashed and hiring markets disappeared.

“You go from being a genius to an idiot in about three months,” he says.

If you visit any company’s website, you’re unlikely to read about moments like this, when everything’s gone wrong. Executives’ bios on “About” pages dependably construct a concurrent narrative in which people go from one success to another. Failure is not part of the story.

But as these alumni from ASU’s W. P. Carey School of Business will tell you, failure inevitably is part of the story. Bad timing, wrong choices, misaligned skillsets, and misunderstood problems all come with the territory when leading a business. As their experience shows, what matters is how we fail, what we learn from it, and how it makes businesses stronger and leadership more capable over the long term.

Take Matos as Exhibit A. Today he is the founder and CEO of Paradox.ai, which provides an assistive intelligence platform that helps companies improve their interview acceptance rates, exceed hiring goals, and reduce hiring time. It serves more than 400 organizations in more than 60 countries. Among them: McDonald’s, Delta Air Lines, and CVS Health.

Scott is the creator of Honest Hazel, a beauty brand that offers hydrating and firming under-eye gel patches now sold at Anthropologie, Nordstrom, Aillea Beauty, Credo, and local beauty boutiques — as well as on Gwyneth Paltrow’s website, Goop. Online and in-person word-of-mouth has also helped the company garner spotlights on The Today Show and in Glamour, Forbes, and Elle.

It all began, says Scott, after a cross-country move for a corporate job that uprooted her family. Within two weeks of relocating she learned of the company’s pending acquisition, and her position was eliminated just months later. When she was told by HR, “This is just business,” Scott thought, “No, this is not just business — this is my family,” and she vowed to leverage her experience in launching and growing social selling companies to create a different kind of company in 2014 — her own. “I will never say, ‘This is business.’ I will be good to people and for people.” The name Honest Hazel (hazel for her eye color) and the tagline “Beautifully Honest” reflect Scott’s business philosophy.

n a society that prides itself on grand plans and historic achievements, human beings have an equal and arguably greater ability to commit awe-inspiring failures. An optimist would say we are constantly improving. A pessimist would argue that we’re better at failure than we are at success.

Professor of Management and Entrepreneurship Matthew Semadeni, who is a Dean’s Council Distinguished Scholar, would tell you that we’re a million times better at failing than we are at success — but that’s why we’re so successful.

The difference between failure and success

“Why don’t we learn from success?” Semadeni asks. “We don’t have the motivation to find out what worked and what didn’t.” As the mantra goes: If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. The result of that, he notes, is that people never learn from their successes, something not true of failure.

When someone fails, it is easier to step back and see what went wrong and what needs to be changed.

“How can we break this pattern of not being able to learn from success?” he asks. “We have to treat success like a failure, so that we can learn from it the way we can learn from failure.”

It’s also fair for alumni to wonder how their alma mater stacks up with other schools, and the role they can play in maintaining or growing their school’s reputation.

Some rankings, such as the U.S. News & World Report’s undergraduate list, judge business schools by reputation, based only on a survey of U.S. business school deans. The Financial Times’ global MBA ranking combines surveys from alumni with quantitative measures from MBA programs, such as employment rates and class demographics.

Most business schools submit information once a year to organizations that judge objective data, such as student GPAs and starting salaries. Many rankings also include data from questionnaires sent to students and alumni. A minimum number of students and alumni must complete the surveys for a school to be included, meaning their participation is imperative for schools hoping to place high in the rankings.

award winners

on never giving up

(BS Accountancy ’79)

Boals joined BCBSAZ in 1971 and served in a variety of capacities, seeing it through numerous years of growth and success. Before beginning his career there, he served four years in the U.S. Air Force. Boals currently serves on the Arizona Biosciences Board, the board of Phoenix Children’s Hospital, and Northern Arizona University’s Innovations Advisory Board. He is a member of Arizona Tech Investors, the Arizona State University President’s Club, and the W. P. Carey School of Business Dean’s Council.

Newspaper closures prompt extra effort from local businesses

ewspaper readership is declining like crazy. There’s a good chance that nobody is reading my column,” quipped humor columnist Dave Barry. He had a point — U.S. newspaper circulation shrank from 60 million in 1994, the year Barry penned his lament, to 35 million in 2018, according to Pew researchers.

For those who recognize the watchdog role of journalism, this decline might look like a dangerous decrease in corporate oversight. That’s why Assistant Professor of Accounting Roger White teamed up with Min Kim, doctoral student of accountancy, to see if firms would become less transparent and less investor-friendly with local newspaper losses.

Local firms didn’t. White and Kim found that firms with at least 50% of their operations located near a defunct paper take extra steps to keep investors informed and rewarded.

Local heroes

“A lot of people believe that small, local newspapers don’t play an important role in the information environment in the United States,” White says, but previous research has shown that “more than half of unique news in this country is generated by small newspapers.” Large news venues comb these local resources, often via algorithm-driven software, and tease out the news that will be elevated to the national stage. As found by a University of North Carolina study that tallied 1,810 newspaper closures between 2004 and 2018, there’re fewer local resources for large news venues to explore.

Newspaper closures prompt extra effort from local businesses

ewspaper readership is declining like crazy. There’s a good chance that nobody is reading my column,” quipped humor columnist Dave Barry. He had a point — U.S. newspaper circulation shrank from 60 million in 1994, the year Barry penned his lament, to 35 million in 2018, according to Pew researchers.

For those who recognize the watchdog role of journalism, this decline might look like a dangerous decrease in corporate oversight. That’s why Assistant Professor of Accounting Roger White teamed up with Min Kim, doctoral student of accountancy, to see if firms would become less transparent and less investor-friendly with local newspaper losses.

Local firms didn’t. White and Kim found that firms with at least 50% of their operations located near a defunct paper take extra steps to keep investors informed and rewarded.

Local heroes

“A lot of people believe that small, local newspapers don’t play an important role in the information environment in the United States,” White says, but previous research has shown that “more than half of unique news in this country is generated by small newspapers.” Large news venues comb these local resources, often via algorithm-driven software, and tease out the news that will be elevated to the national stage. As found by a University of North Carolina study that tallied 1,810 newspaper closures between 2004 and 2018, there’re fewer local resources for large news venues to explore.

he importance of setting performance goals for an organization is evident in years of study in academia and decades of real-life examples in workplaces around the world. Goals motivate: They help improve employees’ performance and keep them focused. There are only positives involved … right?

ASU management professors Mike Baer and David Welsh beg to differ — at least with the notion that there are no downsides to setting employee performance goals. According to their newly published research, the negatives can be real and significant.

“We’re not trying to say that goals are bad, but they’re not the cure-all for what ails employees and companies,” says Baer. “Sticking your head in the sand and saying, ‘They’re all good,’ is not accurate. Managers don’t seem to recognize this, but should.”

In their new paper, “Hot Pursuit: The Affective Consequences of Organization-Set Versus Self-Set Goals for Emotional Exhaustion and Citizenship Behavior” (June 2019), Baer and Welsh challenge the convention that it doesn’t matter who sets an employee’s performance goals. Their research, published in the Journal of Applied Psychology, found that the opposite is the case — and it’s all about emotions.

he importance of setting performance goals for an organization is evident in years of study in academia and decades of real-life examples in workplaces around the world. Goals motivate: They help improve employees’ performance and keep them focused. There are only positives involved … right?

ASU management professors Mike Baer and David Welsh beg to differ — at least with the notion that there are no downsides to setting employee performance goals. According to their newly published research, the negatives can be real and significant.

“We’re not trying to say that goals are bad, but they’re not the cure-all for what ails employees and companies,” says Baer. “Sticking your head in the sand and saying, ‘They’re all good,’ is not accurate. Managers don’t seem to recognize this, but should.”

In their new paper, “Hot Pursuit: The Affective Consequences of Organization-Set Versus Self-Set Goals for Emotional Exhaustion and Citizenship Behavior” (June 2019), Baer and Welsh challenge the convention that it doesn’t matter who sets an employee’s performance goals. Their research, published in the Journal of Applied Psychology, found that the opposite is the case — and it’s all about emotions.

Getting skin in the game motivates extra-mile efforts

Baer and Welsh discovered that when employees aren’t involved in setting a particular goal, their anxiety will rise and their enthusiasm will wane — a powerful one-two punch that can lead to burnout.

And that’s just the beginning: The research also showed the downstream effect that employees will be more likely to shun so-called “citizenship behavior.” They’ll be less likely to go above and beyond by helping other co-workers, staying late, or reaching beyond their assigned duties for the betterment of the organization.

he epic wildfires that ravaged Northern California in recent years have scorched tens of thousands of acres and caused an estimated $16.5 billion in damage. When Hurricane Maria tore through Florida and Puerto Rico in 2017, it was one of the worst humanitarian catastrophes in U.S. history and one of the costliest, with damages hitting nearly $1 trillion.

Disasters both threaten the human population and destroy natural resources, they also tax the nation’s infrastructure and economy.

Put another way: They’re bad for business. Because natural disasters can have such a devastating impact on the economy and an individual organization’s abilities to stay afloat, Assistant Professor of Supply Chain Management Mikaella Polyviou studies how businesses avoid sinking and recover from disruptions to their supply chains.

What is a supply chain disruption?

“We look at a disruption as an interruption in the flow of products, services, or information from a supplier to a buyer,” Polyviou explains, adding that such interruptions are most often caused by natural disasters but could also be brought on by other events, such as a pandemic, labor strikes at ports or factories, or the imposition of tariffs.

Occasionally, disruption can result from something positive, such as a surge in customer demand. “A company might experience an increase in consumer demand but not have the product in inventory or its production capacity is tied up, so it has to do something to build up inventory or capacity quickly,” Polyviou says. Larger companies have built-in backup plans such as excess production capacity or additional supply sources and transportation providers, while smaller ones usually don’t.

he epic wildfires that ravaged Northern California in recent years have scorched tens of thousands of acres and caused an estimated $16.5 billion in damage. When Hurricane Maria tore through Florida and Puerto Rico in 2017, it was one of the worst humanitarian catastrophes in U.S. history and one of the costliest, with damages hitting nearly $1 trillion.

Disasters both threaten the human population and destroy natural resources, they also tax the nation’s infrastructure and economy.

Put another way: They’re bad for business. Because natural disasters can have such a devastating impact on the economy and an individual organization’s abilities to stay afloat, Assistant Professor of Supply Chain Management Mikaella Polyviou studies how businesses avoid sinking and recover from disruptions to their supply chains.

What is a supply chain disruption?

“We look at a disruption as an interruption in the flow of products, services, or information from a supplier to a buyer,” Polyviou explains, adding that such interruptions are most often caused by natural disasters but could also be brought on by other events, such as a pandemic, labor strikes at ports or factories, or the imposition of tariffs.

Occasionally, disruption can result from something positive, such as a surge in customer demand. “A company might experience an increase in consumer demand but not have the product in inventory or its production capacity is tied up, so it has to do something to build up inventory or capacity quickly,” Polyviou says. Larger companies have built-in backup plans such as excess production capacity or additional supply sources and transportation providers, while smaller ones usually don’t.

here’s an old saying that success has many fathers, but failure is an orphan. When things are going well, everyone wants to claim their place in the victory lane. But when life takes a turn, few are willing to own responsibility; instead, most people try to place the blame somewhere else and put the situation behind them as quickly as possible.

While no one wants to stand in front of a crowd and cop to a mistake or slog through a project they know isn’t going to end well, such challenges often provide the greatest lessons, if we take the time to truly process and reflect. But this often means leaning into the full roller coaster of emotions — from fear, loss, and shame to soul-searching and renewed passion.

Here, a few W. P. Carey School of Business alumni — success stories every one — lay bare their lowest moments and the insights they now see in the rearview mirror.

here’s an old saying that success has many fathers, but failure is an orphan. When things are going well, everyone wants to claim their place in the victory lane. But when life takes a turn, few are willing to own responsibility; instead, most people try to place the blame somewhere else and put the situation behind them as quickly as possible.

While no one wants to stand in front of a crowd and cop to a mistake or slog through a project they know isn’t going to end well, such challenges often provide the greatest lessons, if we take the time to truly process and reflect. But this often means leaning into the full roller coaster of emotions — from fear, loss, and shame to soul-searching and renewed passion.

Here, a few W. P. Carey School of Business alumni — success stories every one — lay bare their lowest moments and the insights they now see in the rearview mirror.

or generations, men who’ve needed help with their mental health have been viewed as failures — too soft, too complicated, unable to cope with “real life.” All the more so for minorities, struggling to gain a foothold in American society.

“In our community, there’s a lot of stigma around going to a therapist,” says Darian Hall (BS Business Administration ’03), who is African American. “Even talking about that was seen as weak. We had to put on this mask of being strong all the time, but that’s not real. We’re not strong all the time, and it’s OK to express that.”

This awareness is part of what drove Hall and business partner Elisa Shankle to found HealHaus, a wellness center, café, and community gathering place in the Bedford–Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York. Hall calls it a “one-stop shop for all things wellness and self-care for mind, body, and spirit.”

HealHaus offers everything from yoga and meditation to psychotherapy and beyond. Its mission is to make these treatments and activities accessible to people who traditionally haven’t tapped into such resources by making it not just convenient but also comfortable and acceptable — or, as Hall puts it: “Essentially, we’re making it cool.

“Most therapy offices feel clinical, like you must have something wrong with you to go there,” he says. “Our environment is warm and welcoming — there’s a café, there’s good music.” And perhaps most importantly for men in general and people of color, visitors to HealHaus see practitioners and participants who look like them, so they can see and feel that they belong.

or generations, men who’ve needed help with their mental health have been viewed as failures — too soft, too complicated, unable to cope with “real life.” All the more so for minorities, struggling to gain a foothold in American society.

“In our community, there’s a lot of stigma around going to a therapist,” says Darian Hall (BS Business Administration ’03), who is African American. “Even talking about that was seen as weak. We had to put on this mask of being strong all the time, but that’s not real. We’re not strong all the time, and it’s OK to express that.”

This awareness is part of what drove Hall and business partner Elisa Shankle to found HealHaus, a wellness center, café, and community gathering place in the Bedford–Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York. Hall calls it a “one-stop shop for all things wellness and self-care for mind, body, and spirit.”

HealHaus offers everything from yoga and meditation to psychotherapy and beyond. Its mission is to make these treatments and activities accessible to people who traditionally haven’t tapped into such resources by making it not just convenient but also comfortable and acceptable — or, as Hall puts it: “Essentially, we’re making it cool.

“Most therapy offices feel clinical, like you must have something wrong with you to go there,” he says. “Our environment is warm and welcoming — there’s a café, there’s good music.” And perhaps most importantly for men in general and people of color, visitors to HealHaus see practitioners and participants who look like them, so they can see and feel that they belong.

The local bike shop put him out of business, but from that failure Neuendorff says he learned that funding, marketing, and presence matter. Since then, he’s run other businesses related to music, video, and personal finance. “It’s been a great journey thus far, and I’ve learned that tenacity, creativity, enthusiasm, technology adoption, and total love for your customers all make for a powerful competitive advantage.”

ou are going to fail. It happens to everyone some time or another. How we deal with failure significantly affects our success and, ultimately, our happiness. In my professional experience as a leadership consultant and entrepreneur, I’ve found four lessons to better manage it.

Identify your purpose. Why do you exist? Or, said differently: What kind of productive individual do you want to be? Your answer to this fundamental question will become the standard on how you’ll measure progress and gauge setbacks.

Don’t underestimate the power of this simple but profound exercise. Take the example of Jacob Cohen, a struggling comedian who experienced a constant string of failures in his pursuit of success. He became so disillusioned that he quit comedy for a decade, working a variety of other jobs instead. Keenly aware that he was off-purpose, Cohen returned to comedy at age 46 with a new act and persona. You know him by his stage name: Rodney Dangerfield.

Acknowledge your behaviors. Behaviors, or the manners of action, help explain our responses to failure. I have my clients complete a scientifically validated tool that clarifies “who” they are, with respect to how they instinctively act. It explains a lot. For instance, some behavioral profiles want to win and easily accept failure as a cost of doing business. Sometimes they accept it too easily and don’t learn from it. Others feel they must always be right and technically correct. They can take failure unduly hard and extremely personally.

ou are going to fail. It happens to everyone some time or another. How we deal with failure significantly affects our success and, ultimately, our happiness. In my professional experience as a leadership consultant and entrepreneur, I’ve found four lessons to better manage it.

Identify your purpose. Why do you exist? Or, said differently: What kind of productive individual do you want to be? Your answer to this fundamental question will become the standard on how you’ll measure progress and gauge setbacks.

Don’t underestimate the power of this simple but profound exercise. Take the example of Jacob Cohen, a struggling comedian who experienced a constant string of failures in his pursuit of success. He became so disillusioned that he quit comedy for a decade, working a variety of other jobs instead. Keenly aware that he was off-purpose, Cohen returned to comedy at age 46 with a new act and persona. You know him by his stage name: Rodney Dangerfield.

Acknowledge your behaviors. Behaviors, or the manners of action, help explain our responses to failure. I have my clients complete a scientifically validated tool that clarifies “who” they are, with respect to how they instinctively act. It explains a lot. For instance, some behavioral profiles want to win and easily accept failure as a cost of doing business. Sometimes they accept it too easily and don’t learn from it. Others feel they must always be right and technically correct. They can take failure unduly hard and extremely personally.

he hundreds of thousands of people who flock to Barrett-Jackson’s annual collector car auction under the massive white tents at WestWorld of Scottsdale each January have no reason to know their names. They’re far away from the auctioneer’s staccato urgings as dream vehicles roll across the stage under the bright lights, racking up bids that stretch into the millions of dollars.

But behind the scenes, the contributions of two company executives equipped with a dose of ASU business pedigree are not to be denied.

Call them “the generals,” as in Barrett-Jackson General Manager and Executive Vice President Nick Cardinale (MBA ’14), and General Counsel Matt Ohre (BS Finance ’99). Together, these two Sun Devil colleagues help make sure the mega-event successfully crosses the finish line.

“I tell everybody that I help the CEO oversee everything except the cars,” says Cardinale. “People say, ‘But Barrett-Jackson is a car auction.’ That’s true, but it’s so much more.”

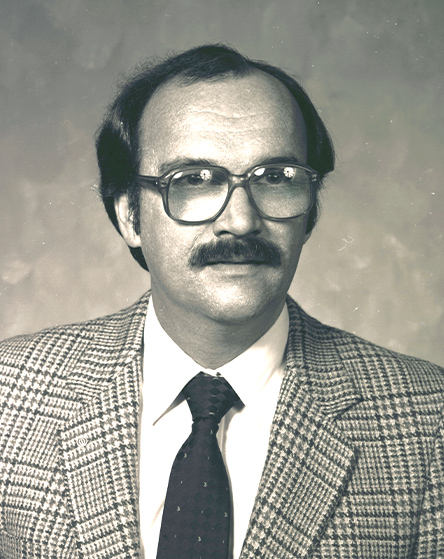

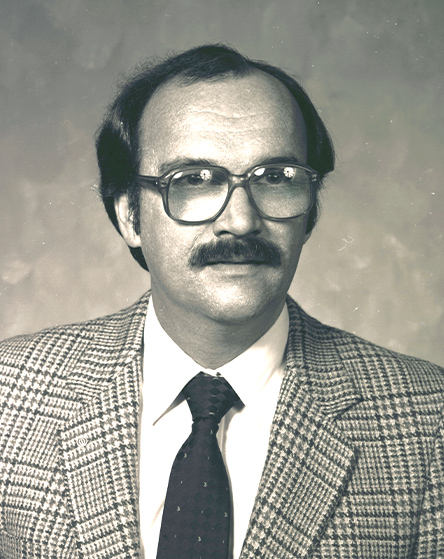

Here’s how former students and fellow faculty remember him:

“He always had a paper or book to write in during our exams, but I didn’t realize until I began working with him that it was sudoku — he loved sudoku!” says Linda Prince (BS Computer Information Systems ’10, MBA ’12)

“He was tough, and the lowest grade I got in my entire CIS program was in his class,” says Belinda Chiu (BS Computer Information Systems ’11). “But the course contained the skills I have used the most since graduation, so I’m glad he was tough.”

Dr. Robert Keim

Dr. Robert Keim

Here’s how former students and fellow faculty remember him:

“He always had a paper or book to write in during our exams, but I didn’t realize until I began working with him that it was sudoku — he loved sudoku!” says Linda Prince (BS Computer Information Systems ’10, MBA ’12)

“He was tough, and the lowest grade I got in my entire CIS program was in his class,” says Belinda Chiu (BS Computer Information Systems ’11). “But the course contained the skills I have used the most since graduation, so I’m glad he was tough.”

Alice M. Ambrose

(BS Accountancy)

1980

Leonard Bowman

(BS Management)

Michael Dorsch

(MBA Business Administration)

Mark Gershaw

(BS Management)

1998

Gregory D. Sabin

(MBA Business Administration)

1991

William J. Hamouz Jr.

(BS Computer Information Systems)

Manuelito M. Lanza

(BS Finance)

2016

Holly Balash

(BA Business Communication)

2019

Gage R. Schrantz

(BS Finance)

Alice M. Ambrose

(BS Accountancy)

1980

Leonard Bowman

(BS Management)

Michael Dorsch

(MBA Business Administration)

1984

Mark Gershaw

(BS Management)

1998

Gregory D. Sabin

(MBA Business Administration)

William J. Hamouz Jr.

(BS Computer Information Systems)

1999

Manuelito M. Lanza

(BS Finance)

2016

Holly Balash

(BA Business Communication)

2019

Gage R. Schrantz

(BS Finance)

Mike O’Dell joined W. P. Carey in 1980 as an assistant professor of accountancy. While here, he was honored extensively for his teaching. He won the 1993 Excellence in Teaching Award from the Arizona CPA Foundation of Education and Research and the 1993 Accounting Circle Outstanding Graduate Teaching Award. In 1995, O’Dell was presented the Governor’s Award of Excellence for his work on the School of Accountancy’s undergraduate curriculum team. He retired in 2004 and continued to serve the school as an emeritus faculty member. Before joining academia, O’Dell served as a captain in the U.S. Air Force. He also worked in real estate and banking before returning to school at the University of Texas at Austin, where he earned his PhD in accounting with a focus in taxation. He died Feb. 14, at the age of 77.

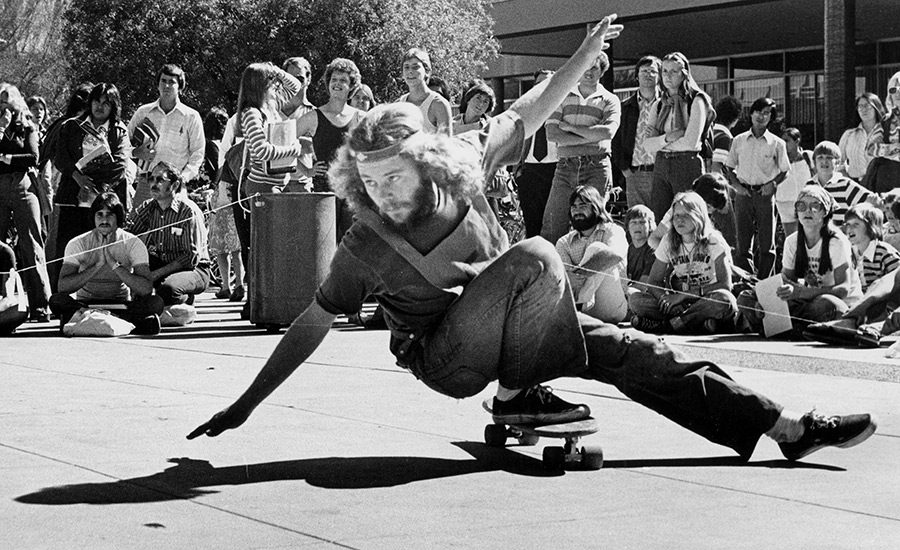

uring President Barack Obama’s commencement address at ASU on May, 13, 2009, he said,

“ … You may have setbacks, and you may have failures, but you’re not done — you’re not even getting started, not by a long shot. And if you ever forget that, just look to history. Thomas Paine was a failed corset maker, a failed teacher, and a failed tax collector before he made his mark on history with a little book called Common Sense that helped ignite a revolution. Julia Child didn’t publish her first cookbook until she was almost 50. Colonel Sanders didn’t open up his first Kentucky Fried Chicken until he was in his 60s.”

With that in mind, we decided to compile some other memorable quotes about setbacks. This list is in no particular order. Can you guess who said what?